Can development corridors deliver positive outcomes for nature?

Diego Juffe Bignoli (Senior Programme Officer, UNEP-WCMC/ Post-Doctoral Scientist, Development Corridors Partnership)

“I don’t want problems, I want solutions” one of my early managers used to tell me more than a decade ago. Ever since, that simple request has followed me as a guiding principle. Of course, you need to know what the problems are before you find solutions, but I feel in many cases, especially in the conservation sector, we pay too much attention to the former and less to the latter. In my new paper, together with expert co-authors, I explore available solutions for the detrimental impacts of development corridors on nature, and propose how gaps can be filled.

What are development corridors again?

Development corridors are large, often transnational and linear, geographical areas targeted for infrastructure investment to help achieve sustainable development. They are not single projects driven by one or two actors. They are multi-project and multi-stakeholder programmes that can take many years and evolve in many ways. For example, the Lamu Port and South Sudan Transport Corridor (LAPSSET) in Kenya includes airports, roads, resort cities, railways, and powerlines. As such, each project will have its own impact assessment, but the combined effects of all these projects together is less well understood. The Development Corridors Partnership (DCP) project has, for the past 3 years, studied the problems and solutions for development corridors in Kenya and Tanzania.

Figure 1 An image taken by Diego Juffe Bignoli when the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) was under construction in Kenya, seen here running through Nairobi National Park. The SGR is now operational (See here for more DCP research on impacts of SGR).

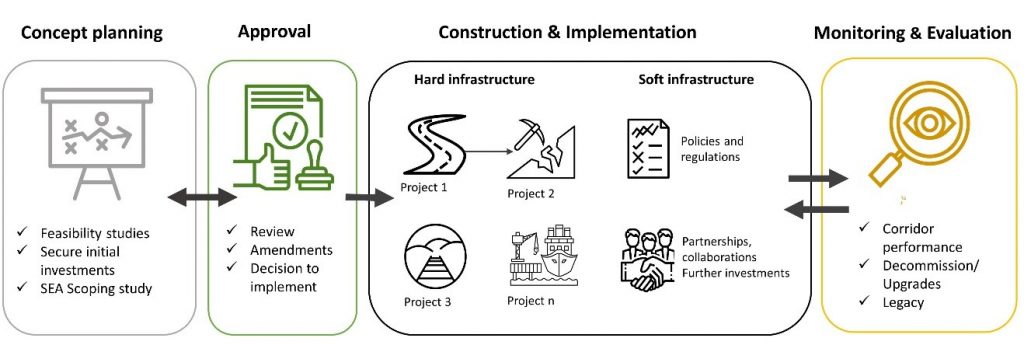

Conceptually a development corridor might run though the same phases any project does: concept planning, approval, construction and implementation, and monitoring and evaluation (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Main phases of a development corridor. Each individual project in the construction and implementation phase will have its own project cycle phases (i.e., conception, design, execution, operation, upgrade, closure or decommission). Specific project level surveys, baseline assessments, feasibility studies, and EIAs are conducted for each of those projects, following the laws and regulations of the countries where they are implemented and complying with the standards and procedures required by lenders.

But development corridors do not behave like single projects. They evolve over time, and rarely start as such. For example, an important mineral resource in a remote area might need a road and a railway to be built to get there, extract the resource, and take it to a port to export it, so that can be called a transport corridor. As hard infrastructure increases, soft infrastructure such as partnerships or new policies might be needed, and then it can become a trade corridor or an economic corridor. As new projects and stakeholders get involved, in the long term, it can become a development corridor. Therefore, our definition of development corridors is an aspirational one. The main attribute of a development corridor should be to aim for sustainability in its broad sense: social, economic, and environmental.

Development corridors might deliver numerous benefits to economies and societies but may also result in long term and serious negative impacts on nature and the benefits that people derive from it. We know that in 2005, at least 33 development corridors where ongoing or planned in Africa alone, and that these posed a threat to over 400 protected areas. Through the Development Corridors Partnership project, we have learned that existing impact assessment on development corridors (i.e., Environmental Impact Assessments and Strategic Environmental Impact Assessments) do not comprehensively assess potential social and environmental impacts. We have also learned that the number of planned corridors in Africa has increased from at least 33 to at least 85 development corridors (work to be published soon). Through our paper we show that the assessments of impacts on biodiversity, and exploration of potential solutions, are particularly poor.

How development corridors impact nature

To explain how corridors might impact nature we need to simplify things a bit. We can identify 3 types of impacts: direct, indirect, and cumulative. Direct impacts relate to what happens when a project is constructed. Cumulative and indirect impacts are more about what may happen in the future because of a project existing in the short and long term. In our mine, road and railway example above, direct impacts would be the effects of the road, mine, and port just by being there: the removal of land, the destruction of migratory routes, or disturbance of rivers. Indirect impacts are those that happen because of the project being there. In our example, people will migrate and settle in that area to work in the mine or port, or to search for new opportunities. They will bring families with them, increasing interactions with the surroundings even more. Cumulative impacts are the combined effects of the indirect and direct impacts of the road, the port, and the mine, as well as impacts that will affect all projects at the same time such as climate change. Research shows that indirect impacts can be four times higher than direct impacts and cumulative impacts and can undermine any action a company takes to avoid impacts, because other companies in the same space will simply not do the same.

In many ways, we understand the issues related to development corridors, but these do not seem to be comprehensively addressed in practice. This is not only in the case of development corridors. It’s a widespread challenge to address how biodiversity impacts are assessed in infrastructure projects through Environmental Impact Assessments and, when they exist, Strategic Environmental Assessments. That is why the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) developed guidelines on how to conduct biodiversity inclusive assessments. It is also why we have reviewed how development corridors have been implemented around the world in our upcoming sourcebook on Impact Assessment, and what the lessons from these case studies are.

Mitigating the impacts of development corridors on biodiversity: a global review

We know there is a well-developed area of work around assessing and mitigating the impacts of biodiversity in individual projects. Moreover, the science of road ecology is backed by historical efforts. Several research groups are also exploring how to achieve positive outcomes for people and nature while meeting development needs. We were also aware of a few papers warning about the negative impacts of development corridors on biodiversity[1], but we wanted to dig deeper to understand what has been explored in peer-reviewed research, specifically on development corridors. So we did.

We reviewed all the scientific literature about development corridors that mentions biodiversity and ecosystem services between 1971 and 2020 to answer 3 questions:

- Do they really assess impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services?

- When they do, what do they measure, how and in which stage of the project?

- Do these methods follow what is considered best practice in impact mitigation science?

Here is what we found

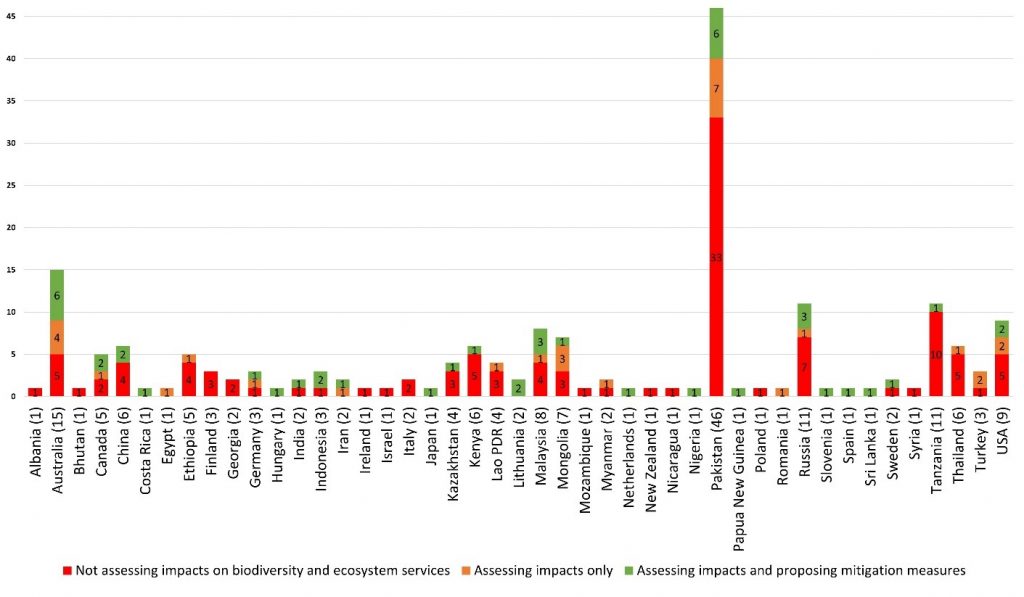

Figure 3 All 45 country case studies divided by: those not assessing impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services (red); those assessing impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services (orange); and those which in addition to assessing impacts and proposing biodiversity mitigation measures to manage those impacts (green). Total number of case studies are in brackets by the country name.

Our global review clearly shows that development corridors are globally widespread but the assessment of their impacts on biodiversity is scarce and simplistic and not many solutions are explored. In short, science needs to catch up to what is needed in practice to implement better and more sustainable development corridors.

We found 270 studies on development corridors mentioning biodiversity or ecosystem services or similar terms in their abstracts. 189 were country level analyses and 82 transnational level (more than one country). 70% of the studies were country specific, covering a total of 45 countries (Figure 3) while 30% took a regional approach. However, only 100 of these assessed impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services and 39 of these did not propose any mitigation measures.

Here are 5 key take home messages of what peer reviewed research on development corridor does (or does not) contain:

- Studies rarely consider biodiversity impacts in a meaningful way and most ignore impacts on ecosystem services: Of 271 studies only 100 (37%) assessed impacts on biodiversity and 7 (3%) addressed impacts on ecosystems services.

- Only 1 in 5 studies proposed solutions: Of those 100 that did assess impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services only half explored mitigation measures to manage those impacts. This is 20 % of the 271.

- Best practice in biodiversity impact mitigation is not followed: scientific studies hardly followed the mitigation hierarchy which is considered as a best practice framework to manage impacts. It proposes four sequential but iterative stages to manage impacts to achieve positive outcomes for nature: avoid, minimise, restore, and offset. We should always direct our effort to the early stages of this framework.

- Studies mostly look at direct impacts only and try to minimise these after they happen: 62% of studies only assessed direct impacts, mostly using buffers to measure indirect impacts and not measuring cumulative impacts and only 37% did this in the conception stage which is when more impacts can be avoided.

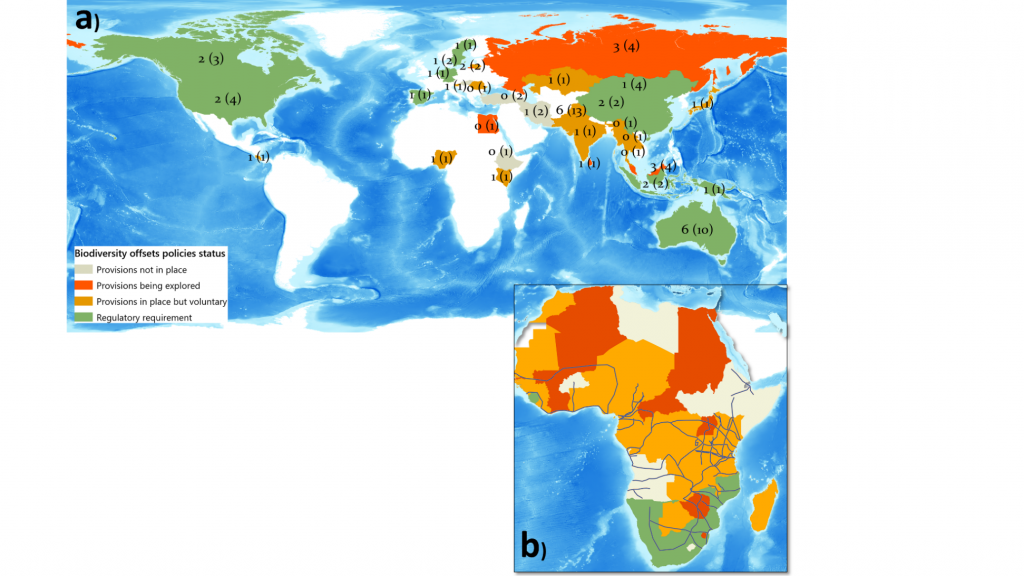

- There are advances in mitigation science and policy instruments that can and should be used: tools and approaches are available to explore the best way to develop the infrastructure we need without destroying nature but the use of these for development corridors is yet to be explored. Strategic Environmental Assessments and Mitigation Policies (see Figure 3) are policy tools that can help take a strategic approach to impact mitigation and pursue the positive outcomes paradigm.

Read our paper to know more!

Figure 4 Number of country case studies proposing biodiversity mitigation measures in each country and, between brackets, total of country case studies. Colours indicate the status of national biodiversity offset policies according to the Global Inventory of Biodiversity Offset Policies (GIBOP 2019), shown for country case studies picked up by our review only. a) Global overview of the results per country of this review. b) Case study for the African continent where blue lines represent 33 ongoing or planned development corridors (Laurance et al. 2015). The map shows that most countries in Africa where development corridors are planned or ongoing have the policy mechanisms in place to pursue better outcomes for biodiversity through ecological compensation.

Mitigating the impacts of development corridors on biodiversity: a global review. Juffe-Bignoli, D., Burgess, N.D., Hobbs, J., Smith, R.J., Tam, C., Thorn, J.P.R., and Bull, J.W. (2021).

Available here: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2021.683949/full

[1] For example, https://mahb.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Laurance-et-al.-2015-African-corridors.pdf and https://apclevenger.weebly.com/uploads/3/0/7/0/30706291/nature_sustainability_bri_ascensao_et_al._2018.pdf